Re-using Raven's password database: Difference between revisions

(Further development) |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

' | Raven currently provides a usable authentication system for interactive, web-based applications but doesn't support non-interactive web-based applications, nor non-web ones, and this excludes many potential uses: Windows/MacOS/Unix logon, IMAP, POP, SMTP, LDAP, WebDAV (and so CalDAV), etc., etc. Since Raven of necessity has a database containing username/password pairs for most people in the University, and most people know their Raven password, it is tempting to assume that extending it to support these other uses would be easy. | ||

Raven | This paper explores ways in which authentication based on 'Raven passwords' could be extended and identifies some of the advantages and drawbacks of each proposal. In reading this, it is important to consider the security properties you might actually want from such a system (hint: it's not important that legitimate users have to provide their password before gaining access to something, what is important is that people can't realistically gain access using an identity that is not their own - these are ''not'' the same thing!). It is also important to consider who might be attempting to attack what, and how much we care about it: are we talking about a) a bored University student, b) a tabloid journalist, c) an organised criminal, or d) the American NSA, and are they trying to gain access to a) their mate's photo archive, b) the next heir to the throne's email account, c) the University financial system, or d) everything. | ||

This paper | This paper only considers ways in which the existing, single Raven password might be usefully reused and ignores possibilities such as as using multiple passwords, one-time password lists, cryptographic smartcards and tokens, fingerprint readers, multi-tier authentication, etc. It also ignores two very real problems with 'static' passwords: | ||

* It is effectively impossible to prevent people giving their password away, and they do! | |||

* Users have to type their password into something - typically the workstation that they are sitting in front of. Depending on the workstation, it is entirely possible that it has been compromised, for example with a virus that installs a key logger or by a malicious or inept system administrator. | |||

==Option the first: forget passwords== | ==Option the first: forget passwords== | ||

Stepping back a bit, we could forget passwords and just ask people what their CRSid is. This would even simplify Raven itself: | |||

[[Image:Simple-raven-login.png|Raven login, no password]] | [[Image:Simple-raven-login.png|center|Raven login, no password]] | ||

This would save people from having a password that they needed to remember, and would save the UCS from having to issue them. Both of these would be significant advantages. Anyone coud easily set up almost any system 'protected' in this way - the hard part might actually be ''stopping'' it from asking for a password. | |||

The obvious downside is that we'd have to trust everyone who can get to a login prompt not to lie (and for many networked services this means everyone in the entire world), and this is rather unrealistic. | The obvious downside is that we'd have to trust everyone who can get to a login prompt not to lie (and for many networked services this means everyone in the entire world), and so this is rather unrealistic. | ||

==Option the second: use a single fixed password== | ==Option the second: use a single fixed password== | ||

Rather than forgetting passwords completely, we could could use a single, fixed, 'well known' password to protect all accounts. | Rather than forgetting passwords completely, we could could use a single, fixed, 'well known' password to protect all accounts. This would be easy to remember (and easy to recover if you forgot it). It would also be fairly easy to set up a system protected in this way. | ||

Now we only have to trust all the people who ever knew the password not to lie. It is fair to assume that a 'secret' legitimately known by 55,000 (and rising) people (those who have ever had a Raven account) would not stay a secret for long so we'd still be trusting quite a lot of people not to lie, if not the whole world. It would also be next to impossible ever to change this password. Again, this is probably not a realistic option (though this doesn't actually stop people using it, though usually on a small scale - think of the codes used to arm and disarm intruder alarm systems). | |||

==Option the third: distribute a list of user name/plaintext password pairs== | ==Option the third: distribute a list of user name/plaintext password pairs== | ||

We could (in theory, though not currently in practice) extract a list of user names and plain text passwords from Raven, one for each user, and then distribute this list to every system that needs to authenticate users. | We could (in theory, though not currently in practice) extract a list of user names and corresponding plain text passwords from Raven, one for each user, and then distribute this list to every system that needs to authenticate users. | ||

Users | Users could then quote their user name and password, the system could look up the the user name and compare the offered password with the one on the list - if it matches they would get in, if not they wouldn't. Implementing authentication in this way would be fairly easy, and system administrators could post-process the list into whatever form their system actually needed. | ||

This | This would avoid having to trust users not to lie - the vast majority of users would only be able to successfully authenticate as themselves. | ||

The list itself, however, | The list itself, however, would now be a major problem. '''''Anyone''''' with access to it could authenticate as '''''any user''''' on '''''any system''''' relying on this authentication service. Worse, since many people use the same password in multiple places, anyone with access to the list could probably also forge authentication on entirely unrelated systems. | ||

All of the managers of all the systems using the authentication service would inherently have access to the list. Even if we | All of the managers of all of the systems using the authentication service would inherently have access to the list, so we would have to trust them. Even if we assume that none of these administrators would ever be actively malicious, there would still the danger that they might accidentally or recklessly leak the list (from a hacked server, on a memory stick, on a laptop left on a train, etc.). So the security of each system under this model would still depend on a whole group of people that each system's administrator has no particular reason to trust. In practice the only option would be to severely restrict the systems that could participate, to the point where such a service could never provide 'universal' authentication for the University. | ||

==Option the fourth: distribute a list of user name/'crypted' password pairs== | ==Option the fourth: distribute a list of user name/'crypted' password pairs== | ||

Rather than distributing plaintext passwords, we could distribute them | Rather than distributing plaintext passwords, we could distribute them 'non-reversibly encrypted' (or 'hashed') - for example using the 'crypt' or 'md5' password format used in Unix password files. In principle this would make it possible to check that a proffered password is correct (by hashing it and checking that the hashed versions match), without exposing all the passwords on the list. | ||

Unfortunately, hashed passwords can be recovered by a 'dictionary attack', in which an attacker generates a dictionary of words and their hashed equivalents and then searches the hashed passwords for matches. Since users have a bad habit of choosing common words (or trivial variations of them) as passwords, such an attack can be expected to recover a reasonable proportion of passwords. So even with hashed passwords the list would be vulnerable to compromise and would still have to be treated as confidential. | |||

In addition, everyone logging-in would still have to offer their plaintext password for verification, at which point it would still be vulnerable given a malicious or negligent system administrator. Consider two systems 'A' and 'B', both using such a system and with some users in common. What grounds can system 'A's administrators have for believing that system 'B's administrators will not (accidentally or deliberately) capture, and disclose or use, user name/password pairs that would allow forged logins on system 'A'. What if system 'A' were on the Student Run Computer System web site and system 'B' was the University Financial System, or vice-versa? | |||

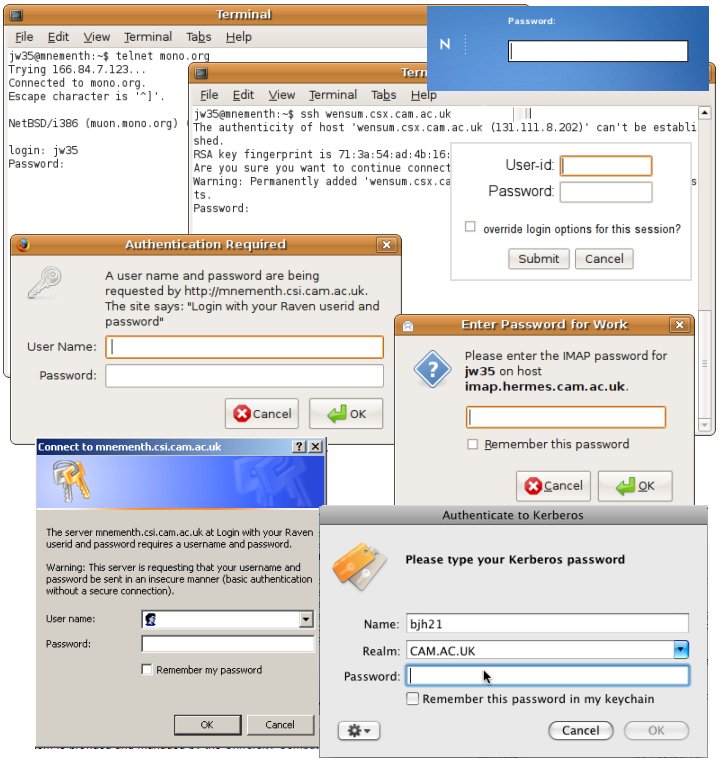

There is unfortunately a more insidious problem. If asked for their 'central authentication system password', how could a user know that it is safe to quote it? Passwords are only safe if you don't disclose them, but to use them that is exactly what you have to do. If you disclose them to a malicious system then you've lost. This is the basis of 'phishing' attacks aimed (with some success) at getting people to disclose the electronic banking or mail system passwords. Given all of the following, which are the bogus sites that is just trying to capture your password? | |||

[[Image:Login-box-montage.jpg|center|Assorted login boxes]] | |||

There is no obvious solution to any of this. | |||

It's worth noting in addition that many authentication schemes (particularly those using some sort of challenge-response) need access to plaintext passwords, or at least particular hashes of the passwords, and so can't be supported by any scheme that distributes pre-hashed passwords. | |||

==Option the fifth: central password verification== | ==Option the fifth: central password verification== | ||

Even if a list could be made to work, distributing it | Even if a list could be made to work, distributing it would be difficult especially if it needs to be done in a timely manner. One solution would be to have a 'central password verification service'. In this model, a system using the authentication service solicits a user name and password for a user and forwards them to the central service which returns a match/no match response. Almost any network protocol could be used for this, but it is common to use LDAP and overload LDAP's 'user login' process to provide authentication. Alternatives include POP, IMAP, RADIUS, and home-grown protocols. | ||

This approach successfully avoids exposing the list of everyone's plaintext or hashed passwords to system administrators (and potentially others) which significantly reduces the exposure. It unfortunately still requires that users's plaintext passwords be disclosed as they authenticate, and does nothing to help users decide when they should and should not quote their password. | |||

Protocols used for remote password verification need to be configured so that they don't expose plaintext passwords on the network, and so the authentication server can't be impersonated and used to collect passwords. Doing this correctly makes things considerably more complicated and is something which is often omitted. | |||

==Option the sixth: Kerberos (or similar)== | |||

Kerberos was designed precisely to overcome many of these problems. It allows a central verification service to assert that a user knows a password, and so has authenticated themselves, without the user having to disclose their password to anything other than their local workstation. It uses assorted cryptographic sleights of hand to do this and has numerous other important properties, such as preventing the recipient of an assertion from using that to impersonate the user on any other service. | |||

In principle Raven could be extended to become a Kerberos central verification service (a 'KDC'). But using Kerberos comes at a cost. Firstly the user's local workstation needs Kerberos software installed and configured. Secondly the Kerberos protocol is significantly more complicated than a user name/password exchange, so unless the systems to be protected already supports it then there are likely to be difficulties. | |||

One interesting development is that Microsoft have adopted Kerberos (or at least, a version of Kerberos) for authentication under Windows. For example every Windows Active Directory Domain is also a KDC. By establishing appropriate trust relationships between Windows KDCs throughout the University it might be possible to use a Raven password to authenticate to an Active Directory Domain and then to rely on Kerberos for further onward authentication as and when required. Similar Kerberos-based login arrangements are available for MacOS and Linux. It is possible that in this environment a malicious or inept AD administrator could compromise authentication - further research is required to establish if it is practical. | |||

Note that this | Kerberos reduces the number of times that passwords need to be entered and so reduces, but does not eliminate, the problem of educating users about when the should and should not provide their passwords when asked. Note that some software (for example this [http://modauthkerb.sourceforge.net/ 'Kerberos' module for Apache]) will misuse the initial Kerberos user authentication process by soliciting the user's user name and plaintext password and then seeing if it can authenticate as the user. In this they are just using the Kerberos system as a central password verification service with all the problems that this entails described earlier. Again, it's not obvious how to enable users to safely detect this. | ||

== | ==Where does Raven fit into this?== | ||

The current Ucam WebAuth system used by Raven, and a whole range of similar web-redirect-based systems, depends on the client software in use being a web browsers and on browsers including as standard a fortuitous combination of features: | |||

* Support for HTTP redirects, allowing the client to be instructed to contact the authentication server direct, allowing communication that bypasses the server initiating authentication; | |||

* Support for the https: protocol, providing both security for the user's password on the wire and a way for users to positively confirm that they are communicating with the real authentication server and not an imposter (and so that it ''is'' safe to disclose their password); and | |||

* Provision of a user interface which can solicit a user and and password. | |||

Ucam WebAuth has some features in common with Kerberos, but without the need to distribute or configure client software, though its use does require much more investment at the server end than a simple user name/password system. It does, crucially, only require the user to disclose their password to the central authentication server and provides a way for users to easily identify it. As a result it, just, manages to provide a reasonably reliable authentication system using passwords, but of course only in a web environment. | |||

Latest revision as of 17:02, 7 January 2009

Raven currently provides a usable authentication system for interactive, web-based applications but doesn't support non-interactive web-based applications, nor non-web ones, and this excludes many potential uses: Windows/MacOS/Unix logon, IMAP, POP, SMTP, LDAP, WebDAV (and so CalDAV), etc., etc. Since Raven of necessity has a database containing username/password pairs for most people in the University, and most people know their Raven password, it is tempting to assume that extending it to support these other uses would be easy.

This paper explores ways in which authentication based on 'Raven passwords' could be extended and identifies some of the advantages and drawbacks of each proposal. In reading this, it is important to consider the security properties you might actually want from such a system (hint: it's not important that legitimate users have to provide their password before gaining access to something, what is important is that people can't realistically gain access using an identity that is not their own - these are not the same thing!). It is also important to consider who might be attempting to attack what, and how much we care about it: are we talking about a) a bored University student, b) a tabloid journalist, c) an organised criminal, or d) the American NSA, and are they trying to gain access to a) their mate's photo archive, b) the next heir to the throne's email account, c) the University financial system, or d) everything.

This paper only considers ways in which the existing, single Raven password might be usefully reused and ignores possibilities such as as using multiple passwords, one-time password lists, cryptographic smartcards and tokens, fingerprint readers, multi-tier authentication, etc. It also ignores two very real problems with 'static' passwords:

- It is effectively impossible to prevent people giving their password away, and they do!

- Users have to type their password into something - typically the workstation that they are sitting in front of. Depending on the workstation, it is entirely possible that it has been compromised, for example with a virus that installs a key logger or by a malicious or inept system administrator.

Option the first: forget passwords

Stepping back a bit, we could forget passwords and just ask people what their CRSid is. This would even simplify Raven itself:

This would save people from having a password that they needed to remember, and would save the UCS from having to issue them. Both of these would be significant advantages. Anyone coud easily set up almost any system 'protected' in this way - the hard part might actually be stopping it from asking for a password.

The obvious downside is that we'd have to trust everyone who can get to a login prompt not to lie (and for many networked services this means everyone in the entire world), and so this is rather unrealistic.

Option the second: use a single fixed password

Rather than forgetting passwords completely, we could could use a single, fixed, 'well known' password to protect all accounts. This would be easy to remember (and easy to recover if you forgot it). It would also be fairly easy to set up a system protected in this way.

Now we only have to trust all the people who ever knew the password not to lie. It is fair to assume that a 'secret' legitimately known by 55,000 (and rising) people (those who have ever had a Raven account) would not stay a secret for long so we'd still be trusting quite a lot of people not to lie, if not the whole world. It would also be next to impossible ever to change this password. Again, this is probably not a realistic option (though this doesn't actually stop people using it, though usually on a small scale - think of the codes used to arm and disarm intruder alarm systems).

Option the third: distribute a list of user name/plaintext password pairs

We could (in theory, though not currently in practice) extract a list of user names and corresponding plain text passwords from Raven, one for each user, and then distribute this list to every system that needs to authenticate users.

Users could then quote their user name and password, the system could look up the the user name and compare the offered password with the one on the list - if it matches they would get in, if not they wouldn't. Implementing authentication in this way would be fairly easy, and system administrators could post-process the list into whatever form their system actually needed.

This would avoid having to trust users not to lie - the vast majority of users would only be able to successfully authenticate as themselves.

The list itself, however, would now be a major problem. Anyone with access to it could authenticate as any user on any system relying on this authentication service. Worse, since many people use the same password in multiple places, anyone with access to the list could probably also forge authentication on entirely unrelated systems.

All of the managers of all of the systems using the authentication service would inherently have access to the list, so we would have to trust them. Even if we assume that none of these administrators would ever be actively malicious, there would still the danger that they might accidentally or recklessly leak the list (from a hacked server, on a memory stick, on a laptop left on a train, etc.). So the security of each system under this model would still depend on a whole group of people that each system's administrator has no particular reason to trust. In practice the only option would be to severely restrict the systems that could participate, to the point where such a service could never provide 'universal' authentication for the University.

Option the fourth: distribute a list of user name/'crypted' password pairs

Rather than distributing plaintext passwords, we could distribute them 'non-reversibly encrypted' (or 'hashed') - for example using the 'crypt' or 'md5' password format used in Unix password files. In principle this would make it possible to check that a proffered password is correct (by hashing it and checking that the hashed versions match), without exposing all the passwords on the list.

Unfortunately, hashed passwords can be recovered by a 'dictionary attack', in which an attacker generates a dictionary of words and their hashed equivalents and then searches the hashed passwords for matches. Since users have a bad habit of choosing common words (or trivial variations of them) as passwords, such an attack can be expected to recover a reasonable proportion of passwords. So even with hashed passwords the list would be vulnerable to compromise and would still have to be treated as confidential.

In addition, everyone logging-in would still have to offer their plaintext password for verification, at which point it would still be vulnerable given a malicious or negligent system administrator. Consider two systems 'A' and 'B', both using such a system and with some users in common. What grounds can system 'A's administrators have for believing that system 'B's administrators will not (accidentally or deliberately) capture, and disclose or use, user name/password pairs that would allow forged logins on system 'A'. What if system 'A' were on the Student Run Computer System web site and system 'B' was the University Financial System, or vice-versa?

There is unfortunately a more insidious problem. If asked for their 'central authentication system password', how could a user know that it is safe to quote it? Passwords are only safe if you don't disclose them, but to use them that is exactly what you have to do. If you disclose them to a malicious system then you've lost. This is the basis of 'phishing' attacks aimed (with some success) at getting people to disclose the electronic banking or mail system passwords. Given all of the following, which are the bogus sites that is just trying to capture your password?

There is no obvious solution to any of this.

It's worth noting in addition that many authentication schemes (particularly those using some sort of challenge-response) need access to plaintext passwords, or at least particular hashes of the passwords, and so can't be supported by any scheme that distributes pre-hashed passwords.

Option the fifth: central password verification

Even if a list could be made to work, distributing it would be difficult especially if it needs to be done in a timely manner. One solution would be to have a 'central password verification service'. In this model, a system using the authentication service solicits a user name and password for a user and forwards them to the central service which returns a match/no match response. Almost any network protocol could be used for this, but it is common to use LDAP and overload LDAP's 'user login' process to provide authentication. Alternatives include POP, IMAP, RADIUS, and home-grown protocols.

This approach successfully avoids exposing the list of everyone's plaintext or hashed passwords to system administrators (and potentially others) which significantly reduces the exposure. It unfortunately still requires that users's plaintext passwords be disclosed as they authenticate, and does nothing to help users decide when they should and should not quote their password.

Protocols used for remote password verification need to be configured so that they don't expose plaintext passwords on the network, and so the authentication server can't be impersonated and used to collect passwords. Doing this correctly makes things considerably more complicated and is something which is often omitted.

Option the sixth: Kerberos (or similar)

Kerberos was designed precisely to overcome many of these problems. It allows a central verification service to assert that a user knows a password, and so has authenticated themselves, without the user having to disclose their password to anything other than their local workstation. It uses assorted cryptographic sleights of hand to do this and has numerous other important properties, such as preventing the recipient of an assertion from using that to impersonate the user on any other service.

In principle Raven could be extended to become a Kerberos central verification service (a 'KDC'). But using Kerberos comes at a cost. Firstly the user's local workstation needs Kerberos software installed and configured. Secondly the Kerberos protocol is significantly more complicated than a user name/password exchange, so unless the systems to be protected already supports it then there are likely to be difficulties.

One interesting development is that Microsoft have adopted Kerberos (or at least, a version of Kerberos) for authentication under Windows. For example every Windows Active Directory Domain is also a KDC. By establishing appropriate trust relationships between Windows KDCs throughout the University it might be possible to use a Raven password to authenticate to an Active Directory Domain and then to rely on Kerberos for further onward authentication as and when required. Similar Kerberos-based login arrangements are available for MacOS and Linux. It is possible that in this environment a malicious or inept AD administrator could compromise authentication - further research is required to establish if it is practical.

Kerberos reduces the number of times that passwords need to be entered and so reduces, but does not eliminate, the problem of educating users about when the should and should not provide their passwords when asked. Note that some software (for example this 'Kerberos' module for Apache) will misuse the initial Kerberos user authentication process by soliciting the user's user name and plaintext password and then seeing if it can authenticate as the user. In this they are just using the Kerberos system as a central password verification service with all the problems that this entails described earlier. Again, it's not obvious how to enable users to safely detect this.

Where does Raven fit into this?

The current Ucam WebAuth system used by Raven, and a whole range of similar web-redirect-based systems, depends on the client software in use being a web browsers and on browsers including as standard a fortuitous combination of features:

- Support for HTTP redirects, allowing the client to be instructed to contact the authentication server direct, allowing communication that bypasses the server initiating authentication;

- Support for the https: protocol, providing both security for the user's password on the wire and a way for users to positively confirm that they are communicating with the real authentication server and not an imposter (and so that it is safe to disclose their password); and

- Provision of a user interface which can solicit a user and and password.

Ucam WebAuth has some features in common with Kerberos, but without the need to distribute or configure client software, though its use does require much more investment at the server end than a simple user name/password system. It does, crucially, only require the user to disclose their password to the central authentication server and provides a way for users to easily identify it. As a result it, just, manages to provide a reasonably reliable authentication system using passwords, but of course only in a web environment.